Historical Figures of Kirkbean

Despite its small size, Kirkbean Parish which is situated in a beautiful corner of south-west Scotland is the birthplace of a number of notable historical figures, the best known of whom is perhaps the father of the United States Navy, John Paul Jones.

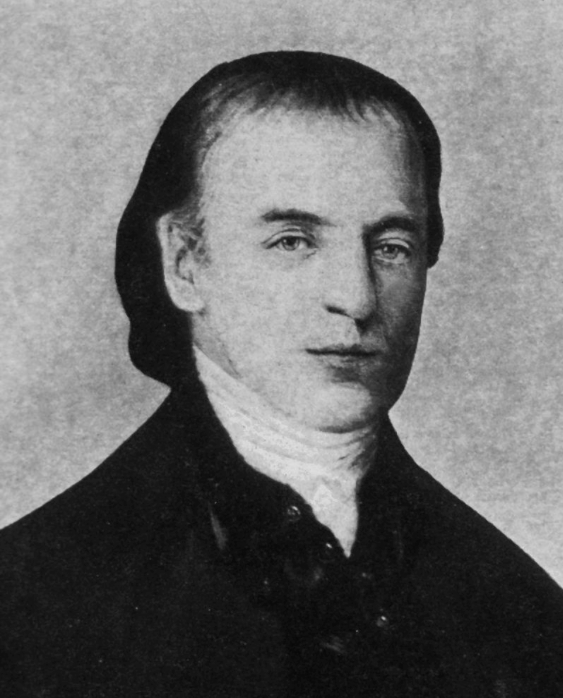

John Paul Jones

Father of the United States Navy (1747-1792)

Undoubtedly, one of Kirkbean’s most famous sons is John Paul Jones, "Father" of the United States Navy, who was born on July 6th, 1747, in a cottage in the grounds of the Arbigland estate, southeast of the village.

John Paul (who added Jones to his name in later life) was the son of a gardener at Arbigland. His parents John Paul (Sr.) and Jean Duff married on November 29th, 1733, in the neighbouring parish of New Abbey. John Paul started his maritime career at the age of 13, sailing out of Whitehaven in the county of Cumberland, as apprentice aboard the “Friendship” under Captain Benson. His older brother had married and settled in Virginia, the destination of many of John Paul’s early voyages.

For several years, John Paul sailed aboard a number of different merchant and slaver ships, but after a short time in this business, he became unhappy with the cruelty in the slave trade and, in 1768, whilst in port in Jamaica, he found passage back to Scotland to find another position.

During his next voyage, the young John Paul’s career quickly advanced when, by chance, both the captain and a ranking mate suddenly died of yellow fever, leaving John to successfully navigate the ship back to a safe port. The vessel's owners appointed him master of his own crew.

But his reputation was to suffer equally as quickly as he had advanced in his career when he was accused of cruelty to a deck hand, then, in another incident, killed a member of his crew, a mutineer, with a sword in a dispute over wages. He later claimed he had acted in self defence. Fearing he would be tried for murder, he felt compelled to flee to Virginia, leaving his fortune behind.

Historians believe he took the surname Jones for disguise. Because of his merchant navy experience, the Continental Congress commissioned him a lieutenant in 1775 and promoted him to captain the following year.

Cruising as far north as Nova Scotia, he took more than 25 prizes in 1776.

It was in Europe, however, that Jones won lasting acclaim. In 1777, he sailed to France in the Ranger and in Paris, he found American diplomat Benjamin Franklin sympathetic to his strategic objectives: hit-and-run attacks on Britain. Early in 1778, Jones attacked the port of Whitehaven, where his seafaring career began.

France became America's ally, but Jones had to be satisfied with a good deal less than he had hoped for in men and ships. With an old vessel renamed Bon Homme Richard (in honour of Franklin) as his flagship, in the summer of 1779, Jones led a small squadron around the coasts of Ireland and Scotland, taking several small prizes.

Then, off the coast of Flamborough Head on September 23rd, he fell in with a large British convoy from the Baltic, escorted by the Serapis (50 guns) and the Scarborough (20 guns).

The most spectacular naval episode of the Revolution followed - a duel between the Bon Homme Richard and the Serapis, a new copper-bottomed frigate. In the ensuing battle, Jones and his crew managed to board the Serapis, take it over and sail for Holland.

He made a final visit to the United States in 1787, when Congress unanimously voted to award him a gold medal for his outstanding services. He was the only naval officer of the American Revolution thus honoured. Soon afterwards, he accepted a commission in the Russian navy and was put in command of a Black Sea squadron with the rank of rear admiral before returning to France where he died.

In 1905, Jones' body was ceremonially removed from his interment in a Parisian charnel house and brought to the United States aboard the USS Brooklyn, escorted by three other cruisers.

On April 24th, 1906, Jones's coffin was installed in Bancroft Hall at the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, following a ceremony in Dahlgren Hall, presided over by President Theodore Roosevelt who gave a lengthy tributary speech.

On January 26th, 1913, the Captain's remains were finally re-interred in a magnificent bronze and marble sarcophagus at the Naval Academy Chapel in Annapolis.

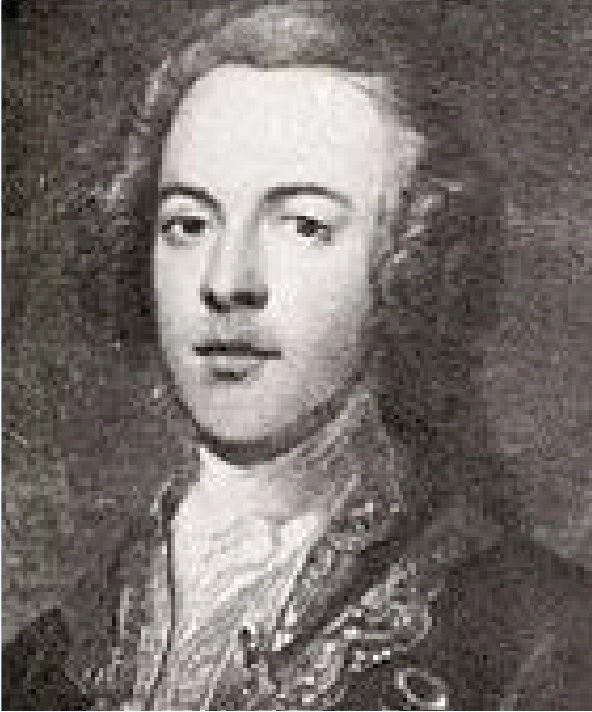

James Craik

George Washington's Personal Physician (1730-1814)

James Craik was born at Arbigland in 1730 and went on to become Physician General (precursor of the Surgeon General) of the United States Army as well as George Washington's personal physician and close friend.

He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, then joined the British Army after graduation, serving as an army surgeon in the West Indies until 1751. Craik then opened up a private medical practice in Norfolk, Virginia.

James Craik George Washington's Personal Physician (1730-1814) born near Kirkbean at Arbigland

On 7th March, 1754, Craik resumed his military career, accepting a commission as a surgeon in Colonel Joshua Fry's Virginia Provincial Regiment. While with this force, he became good friends with George Washington, at that time a lieutenant colonel in the regiment. Craik saw a great deal of action in various battles of the French and Indian War. He fought at the Battle of the Great Meadows and participated in the surrender of Fort Necessity, then accompanied General Edward Braddock on the latter's unsuccessful attempt to recapture the region in 1755, treating Braddock's ultimately fatal wounds.

Craik then served under Washington in actions in Virginia and Maryland, during various engagements with Indians.

With the outbreak of hostilities during the American Revolution, Craik once more rejoined the army. He served as an army surgeon, ultimately advancing to the second-highest post in army medicine. Craik warned Washington about the plots of the Conway Cabal and treated the wounds of General Hugh Mercer at the Battle of Princeton and Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette, at the Battle of Brandywine. Mercer died of his wounds, but La Fayette was more fortunate.

Washington summoned Craik out of private practice in 1798 in connection with the Quasi-War against France, installing him as Physician General of the Army on June 19th of that year. After the conclusion of hostilities, Craik mustered out on June 15th, 1800.

As Washington's personal physician, Craik was one of three doctors to attend him during his final illness on December 14th, 1799.

Craik died in Alexandria in 1814. He is buried in the graveyard of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House there.

John Campbell

Commander-in-Chief of Newfoundland (1720-1790)

Although somewhat overshadowed by his more famous seafaring rival, John Campbell, born in 1720 in Kirkbean, became a British naval officer, navigational expert and colonial governor.

Campbell joined the Royal Navy at an early age and sailed around the world in 1740 on The Centurion.

He later became known as a navigational expert and was, from 1782 till his death, Governor and Commander-in-Chief in Newfoundland. HMS Centurion was a 60-gun fourth-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, built at Portsmouth Dockyard and launched on January 6th, 1732.

John Campbell’s father was minister of Kirkbean and John was, at an early age, apprenticed to the master of a coasting vessel. That vessel's mate was pressed into the navy and John is said to have entered the navy by offering himself in exchange for him.

He served for three years on The Blenheim, Torbay and Russell before being appointed in 1740 as a midshipman to The Centurion where he was promoted to master's mate after The Centurion's ensuing circumnavigation of the world. He was soon promoted to master after the 1743 engagement against the Manila galleon, Nuestra Señora de Covadonga.

In 1745, Campbell passed the examination for lieutenant and soon gained a first command. In 1747, he was promoted to post of captain of the new frigate, Bellona and, in 1749, he was given command of the expedition to the Pacific.

His next commands after The Bellona were the Mermaid, The Prince (90 guns) and - in 1757 - The Essex (64 guns). During his command of The Essex, in 1756, Campbell gave a sea trial to Tobias Mayer's new lunar tables and reflecting circle, trials which would profoundly influence marine navigation for the next 250 years.

Campbell returned to The Royal George as flag captain in November 1759, this time under Hawke (when Hawke moved his flag to that ship), serving as such during the decisive battle of Quiberon Bay on November 20th, 1759.

Next, Campbell was to captain The Dorsetshire (70 guns), on the home station and in the Mediterranean from 1760 to the peace in 1763. He was admitted as a fellow of The Royal Society on May 24th, 1764 (and was one of its Visitors to the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, from March 1765), before being one of those the Board of Longitude asked to 'number-crunch' the results of the 1764 second sea-trial to Barbados of John Harrison's longitude watch.

From about 1764, he commanded the royal yacht Mary, later moving to HMY Royal Charlotte, a command he retained until promotion to rear-admiral of The Blue on January 23rd, 1778. Then, in March 1778, he was chosen to be "captain of the fleet" and effectively, chief of staff in HMS Victory, which commissioned in May 1778.

In 1782, Campbell was appointed governor and commander-in-chief of Newfoundland. He held this post from 1782 to his death at his house at Charles Street, Berkeley Square, London, on December 16th, 1790.

EDWARD MILLIGAN MD

Distinguished Lecturer in Medical Science (1786-1833)

Whilst not as famous as other sons of Kirkbean, Dr Edward Milligan was, nevertheless, a striking example of what can be achieved in the face of adversity.

Edward Milligan was born in the parish in 1786 and spent most of his working life in the humble occupation of shoemaking before gaining distinction as a lecturer of medical science in Edinburgh. A largely self-taught linguist and mathematician, he earned sufficient funds to pay his way through college and after much patient toil teaching himself and others, he acquired not only great eminence among the learned, but also a considerable fortune.

More remarkably, however, much of this was achieved whilst he was completely blind. Such was his strength of mind, his cheerfulness continued unimpaired and he continued his course of lectures with great success until his last illness claimed his life in 1833, aged just 47.

A large monument with an urn to his memory was erected in Kirkbean church yard with the inscription:

Edward MILLIGAN, MD

born in this parish 1786 and died 1st December 1833.

A Man of general erudition embracing even the abstrusest studies.

Remarkable for application, memory & classical taste;

An able Mathematician & a renowned Teacher of the theory of Medicine;

The Architect of his own status in society

Who left behind him fortune as well as fame;

one who, in short, opened for himself a path to distinction

amidst obstacles as formidable as the compact granite of his native Criffel.

Filio. Suos in parentes valde pio, Erga omnes benevolo, sed amicia amicissimo Artis.

Medicae aliarum que pertissimo pater moerens hoc monumentum posuit.

Helen Craik

Poet and Novelist (1751-1825)

Scottish poet and novelist Helen Craik was born at Arbigland c1751. One of six legitimate children, Helen’s father, politician and laird William Craik, was also rumoured to be the father of John Paul Jones.

Helen became a correspondent to Robert Burns. Two of Burns’ letters to her have survived. In 1792, she suddenly moved from Arbigland to Flimby Hall in Cumberland following the purported suicide of a groom on her father’s estate. It is thought that the groom had been engaged to marry Helen, but had been murdered by a member of her family. If true, these dramatic event were echoed in her five novels which were published anonymously.

Her novels were Adelaide de Narbonne, Julia de St. Pierre, Stella of the North or The Foundling of the Ship, The Nun and her Daughter or Memoirs of the Courville Family and Henry of Northumberland or The Hermit's Cell, which was the only one of her novels not set in her own time.

Craik eventually inherited a half-share in the Flimby estate, but no part of her father's at Arbigland which went to a distant male relative, John Hamilton.

She died unmarried at Flimby Hall on June 11th, 1825. Her obituaries and the memorial in her village church describe her as a published author in English and French (works in the latter language have not survived) and a philanthropist to the poor, a theme which appears in her novels.